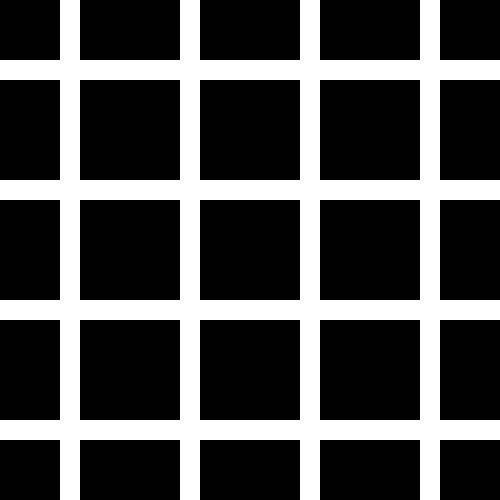

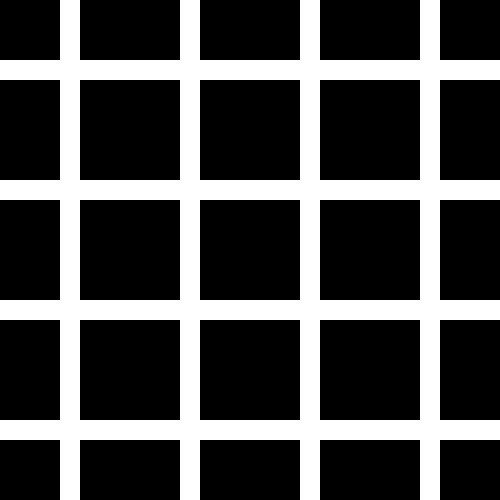

This image is called the Hermann grid. It’s an optical illusion. To experience it, stare at the intersections between the black squares. Do you see it?

When you focus on a single intersection, it becomes white. As you focus on a single intersection the others in your peripheral vision turn gray.

Focus on a different intersection on the grid. Is it white or gray?

It’s white.

Why does the color of an intersection change when observed? What does experiencing this optical illusion tell us about how our mind interprets information?

Scientists say lateral inhibition or light constancy explains the visual phenomenon that the Hermann grid produces. But I am not concerned with explaining why the phenomenon happens—No, I wanted to illustrate, in real-time, the incomplete way the human mind processes information because it shows how we create reality.

Myth as a Way of Navigating the Mind’s Reality

A myth is a symbolic, usually religious, story of uncertain origin. In Western academia, the definition of myth isn’t fixed. Like myths themselves, the definition of myth is fluid and subject to change based on cultural context. Like the visual phenomenon of the Hermann grid, myths reflect our incomplete understanding of the world and what our mind does to fill in the gaps in knowledge.

Today, we know rain isn’t caused by a water goddess, but by the water cycle, a process of evaporation and condensation caused by natural weather systems, sans human form. It’s easy to dismiss early humanity’s explanations of natural phenomena. These explanations seem childlike to the modern mind.

But myths of deities controlling the weather come from a time when sophisticated weather tools and analyses didn’t exist. Water goddesses and thunder gods were a convenient way to explain a gap in human understanding. These myths related human experience to the greater mysteries of the world with the information at hand and an imagination unburdened by objective facts.

And although myth as a mode of explaining the world may seem naive in a world of big data and artificial intelligence, it is still the best explanation for many things we haven’t figured out, like the nature of the universe or the meaning of life.

We know myths are fictional, but if we suspend our critical minds, we can’t help but glean wisdom from these stories despite their fantastic elements. It’s why, as a culture, we still praise stories like The Odyssey.

In general, our minds still process information how our modern ancestors did. We have more tools to collect, organize, and interpret data, but our minds themselves are still remarkably similar to those of the people who believed a humanoid God with electric bolts and a bad temper caused lightning.

Today, science can objectively explain most of what we experience. But science is still one step removed from human understanding because it cannot change how we experience something, only how we understand our experience.

Again, consider the Hermann grid. Science explains why we see gray where there is white, but this knowledge doesn’t stop our minds from seeing gray where white exists.

Like science, myth can also change how we understand our experiences. I think it can also change how we experience something. Imagine how your life experience would change if you believed a god could strike you down with lightning.

Myth changed how the ancient Greeks experienced and understood lightning. And while lightning is something we now objectively experience—We understand what it is, where it comes from, and what it does—it still scares the shit out of us: our experience doesn’t change.

Thanks to science, there are many things we experience objectively now. Shooting stars, earthquakes, and wildfires to name a few. Because of all the information around us, it’s easy to believe that there aren’t any more natural mysteries, or at least very few.

But that’s not true.

Let’s look at an example to make things simpler.

Modern Myth for Primitive Problems

I’m reading Tom Robbins’ Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.

It’s a fun, light-hearted, and traumatically insightful book. It’s completely fictitious, yet it contains some of the most profound tidbits of wisdom I’ve ever read.

The novel brings the unique way humans fill gaps in their understanding to the fore through humor, history, storytelling, wordplay, and more. It challenges us to see the mundane in a new way and promotes a deeper, more human understanding of our reality: It’s a modern myth.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

“A book no more contains reality than a clock contains time. A book may measure so-called reality as a clock measures so-called time; a book may create an illusion of reality as a clock creates an illusion of time…”

This quote demonstrates how myth, or at least good writing, changes the way we experience and understand things we believe to understand objectively: books and clocks.

Two mundane objects—everyone knows what they are. Yet, when we consider these objects’ functions, we are reminded that we know very little about the phenomena that influence our existence, such as reality and time.

We can measure, test, and collect data about reality and time, but any objective metrics we collect won’t define reality or time.

I could reanimate Einstein or Stephen Hawking to explain time to you using the highest degree of scientific precision, and the eight-hour workday would still feel like an eternity.

Myth is relevant today because it tells us things we only partially understand in a playful way that stimulates our curiosity. Lines like Robbins’ pull us away from the seduction of certainty that science offers us, reminding us of our humanity and demonstrating the power myth has to inform and educate.

Science is wonderful, beautiful, and necessary, but its charisma is deceiving. Without question, science tells us many things accurately and authoritatively. But how can we trust ourselves to understand what science tells us when our minds can’t differentiate white from gray?

Burn the Labs! Science is a False God!

Hold on.

Let’s look at the Hermann grid one more time.

The intersections are still gray.

Objectively they’re white.

But we are subjective creatures: our minds are imperfect.

We need science and myth (and much more) to fill in our gaps in understanding.

Our subjective experience informs our reality. Myth understands this and attempts to explain the objective world to us as it filters through our minds, emotions, culture, and experiences.

Myth helps us fill in the gaps in our understanding by challenging objectivity with the authenticity of our humanity. It is not an outdated mode of understanding or a replacement for other modes of understanding, but a perfect solution to an impossible task: making us objective creatures.

Subscribe for poems and interesting reads.